A long time ago, I was getting groceries with my girlfriend. It was shortly

after the first snow, so the grocery store had pallets of windshield washer

fluid ready for the taking buying. It was cheap and I thought it would be

fun to purify, so I chose to get some. I was deeply wrong.

I had known for a while that windshield washer fluid often contained methanol, sometimes ethylene glycol. Both species serve to depress freezing point of the aqueous mixture so as to be usable during freezing temperatures and to de-ice windshields. I also knew that methanol and water are miscible, but do not form an azeotrope, so the two would be separable by distillation. With these facts in mind, I began to eye windshield washer fluids for the right price and concentration.

The moment I saw the pallets of windshield washer fluid in this store, though, I knew there was something different about them. The bulk quantity laid out in front of me, the season creating market demand. The context surrounding me combined into what I felt was a budding garden of flowers on a sunny spring day. With my girlfriend at my side and just before checking out of the store, I eagerly found the safety data sheet to make sure this was my fluid. To my surprise, my girlfriend did not blush from my prowess.

The safety data sheet showed roughly 30% methanol by mass, and the sticker price showed $5. It was truly a score compared to the fluids I had seen in passing.

I quickly turned to my girlfriend. “One moment.” I spedwalk to the nearest pallet and slid between other shoppers, grabbing the fluid and returning to the self-checkout. “It's cheap methanol. You just have to distill it and then it's perfectly fit for reactions.” My girlfriend of developing chemical literacy, upon hearing me utter the phoneme sequences “meth,” “distill,” and “reaction,” hushed me at the self-checkout. I complied and scanned it along with the rest of our groceries, only with a statistically significant grin on my face.

Eventually I had time to distill my methanol. I guessed that a fractional distillation would be required, given that ethanol requires a fractional distillation and has only one more carbon. Thus, I setup for a distillation using my Vigreux column and poured some of the fluid into my boiling flask before turning on my hotplate stirrer.

New Hotplate '%20xmlns:inkscape='http://www.inkscape.org/namespaces/inkscape'%20xmlns:sodipodi='http://sodipodi.sourceforge.net/DTD/sodipodi-0.dtd'%20xmlns='http://www.w3.org/2000/svg'%20xmlns:svg='http://www.w3.org/2000/svg'%3e%3cdefs%20id='defs2'%20/%3e%3csodipodi:namedview%20id='namedview2'%20pagecolor='%23505050'%20bordercolor='%23eeeeee'%20borderopacity='1'%20inkscape:showpageshadow='0'%20inkscape:pageopacity='0'%20inkscape:pagecheckerboard='0'%20inkscape:deskcolor='%23505050'%20inkscape:zoom='41.027778'%20inkscape:cx='18'%20inkscape:cy='17.987813'%20inkscape:window-width='3200'%20inkscape:window-height='2000'%20inkscape:window-x='0'%20inkscape:window-y='0'%20inkscape:window-maximized='1'%20inkscape:current-layer='svg2'%20/%3e%3cpath%20fill='%238899A6'%20d='M15%209l6-6s6-6%2012%200%200%2012%200%2012l-8%208s-6%206-12%200c-1.125-1.125-1.822-2.62-1.822-2.62l3.353-3.348S14.396%2018.396%2016%2020c0%200%203%203%206%200l8-8s3-3%200-6-6%200-6%200l-3.729%203.729s-1.854-1.521-5.646-.354L15%209z'%20id='path1'%20style='fill:%23000000;fill-opacity:1'%20/%3e%3cpath%20fill='%238899A6'%20d='M20.845%2027l-6%206s-6%206-12%200%200-12%200-12l8-8s6-6%2012%200c1.125%201.125%201.822%202.62%201.822%202.62l-3.354%203.349s.135-1.365-1.469-2.969c0%200-3-3-6%200l-8%208s-3%203%200%206%206%200%206%200l3.729-3.729s1.854%201.521%205.646.354l-.374.375z'%20id='path2'%20style='fill:%23000000;fill-opacity:1'%20/%3e%3c/svg%3e) 2.1

2.1

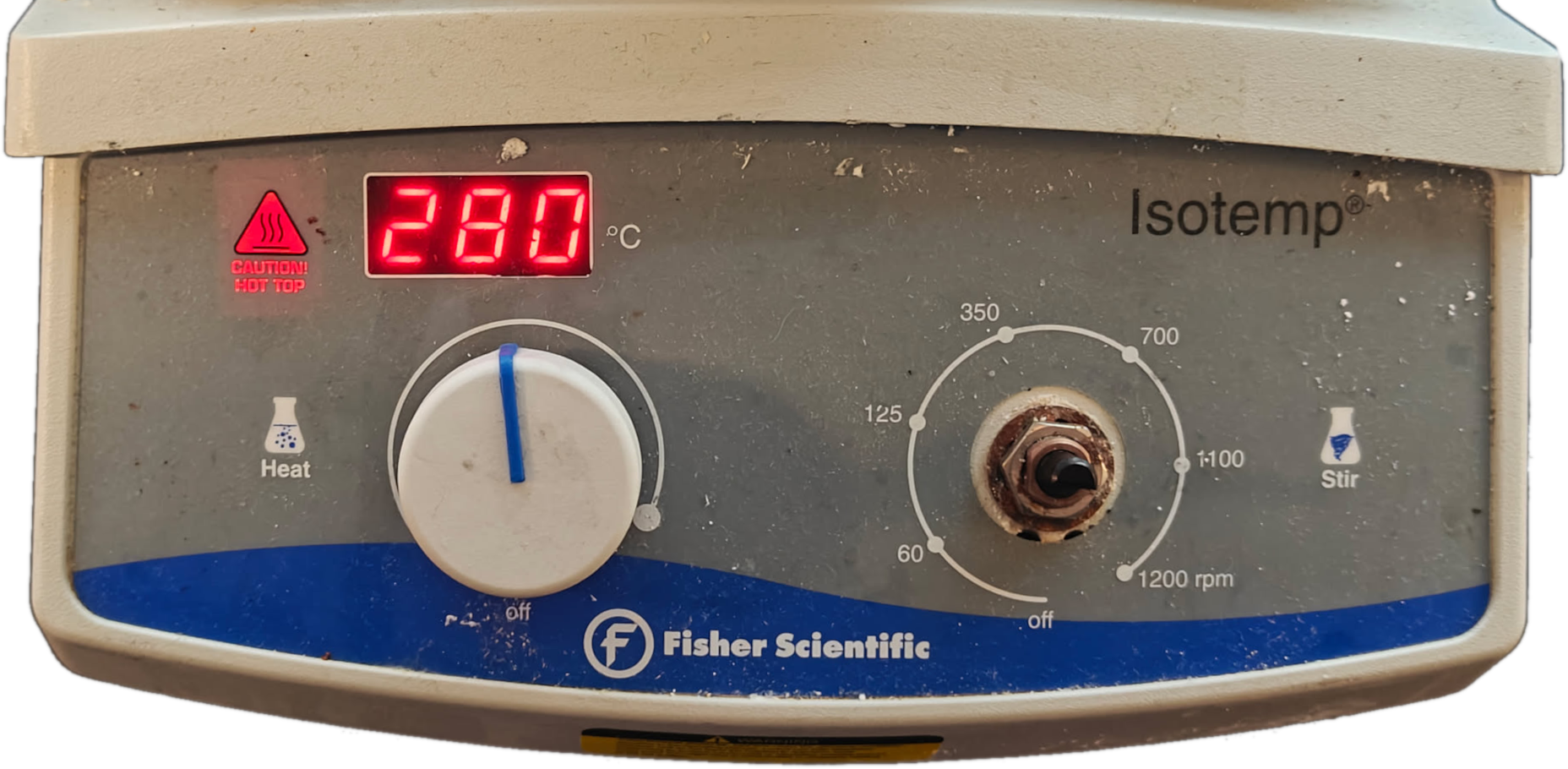

Admittedly, the first problem was entirely unrelated to the methanol. I had just gotten my hotplate stirrer a few weeks before and was figuring out how to perform distillations. Notably, I had done only one distillation without a lab manual that specified the exact position to set a heating knob at, and that distillation became a smoking disaster (literally). I had planned to practice using the hydrous methanol I bought.

For this distillation, I was using a hot air bath: I placed the flask slightly above the hotplate and wrapped aluminum foil around it with a slight skirt. This configuration avoids the issues and potential hazards of an oil bath, but caused the heat of the flask to fluctuate due to air having poor heat capacity and leaking from the foil skirt. The finicky heating played into my next issue.

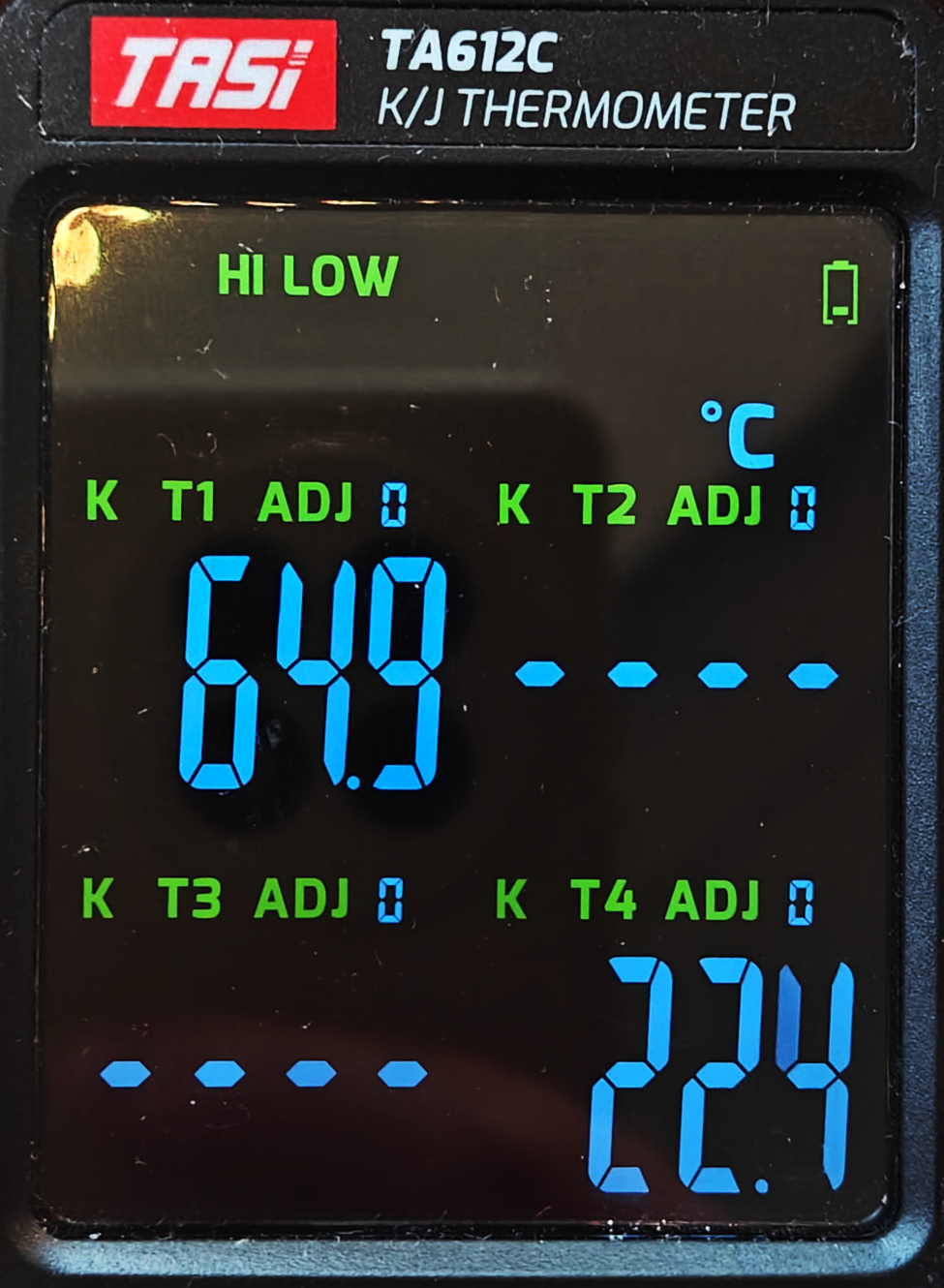

While distilling, I noticed the vapors were slightly above the boiling point of methanol. The temperature stayed steady for a while so I thought perhaps my thermometer needed calibration, but the temperature began to rise. I now believe this was a symptom of flooding the Vigreux column: the initial vapors were largely methanol, so the boiling mixture became enriched in water. Water has a higher boiling point than methanol, so the later vapors coming from the water-enriched mixture came over hotter.

I could not find a solution to this problem. My notes indicate I tried many different heating settings over many hours, as well as blowing a desk fan on the column at different angles and settings to increase the number of revaporizations:

↑ revaporizations ⇒ ↑ methanol concentration ⇒ ↓ vapor temperature

About three seasons later, I have returned to my windshield washer fluid methanol. I need it to perform a recrystalization, so I need to ensure it's anhydrous. Since then I've gotten a hotplate with more precise and responsive temperature control, as well as a thermocouple which allows me to precisely measure vapor temperatures and detect fluctuations.

I had also performed a good number of distillations at this point, around half being fractionating to strip aqueous azeotropes from pure solvent.

I began fractionally distilling my windshield washer fluid but I kept experiencing the same column flooding as before, despite my added experience. In my frustration I tried refitting all my joints with mild force, and I believe this is why I became encumbered with sadness.

My immaculate Vigreux column became slightly cracked on the outside. I'm still using it to redistill methanol as I type this, and I'll probably continue to use it, but I'm pissed that I cracked glassware over distilling a solvent I can buy anhydrous on Amazon for cheap.

I set out to distill methanol for practice so I would not fail a distillation of more important or expensive compounds, so I deem this project a success. I have since distilled reactions mixtures and even stripped solvent under vacuum, and have not failed because I am comfortable with the process. I only wish I did not break my Vigreux column.

However, I recommend against distilling specifically methanol. Find a more interesting compound to distill that's harder to come by! Nitromethane is a niche solvent which refracts light in an interesting way and can be used in the historical nitroaldol condensation. Unlike methanol, it is not available to consumers in a pure form. This makes it an excellent material to practice distillation on, as the end result is still interesting.